Outbreak Investigation Day: A sneak-peek into our potential future as epidemiologists

Happy almost-spring! The sun is still shining outside and the days are most definitely getting longer here. And as the days get longer, so has my motivation to study (and to write this blog post!). To commemorate these two events, I’ll be sharing some moments from the first half of the second semester of the Public Health Sciences (PHS) Masters Program with you all!

The great class split-up…

From the end of January through mid-February, the PHS students split up into their respective tracks for the first time. While my coursemates from the Health Promotion and Prevention (HPP) track were taking a course on Planning and Program development, the Epidemiology track students took a course in Applied Epidemiology. For more information about the PHS programme’s courses, be sure to visit the programme syllabus page. In this course, we were introduced to different surveillance systems and models used on a local, national, and international level. We mainly focused on systems that surveilled communicable and infectious disease outbreaks. It was especially interesting and a bit nostalgic for me, given my previous work experience with infectious disease surveillance.

In this blog I will be highlighting one of the most memorable in-course activities: an outbreak investigation workshop! I hope to convey some moments of excitement and panic, as well as moments where we needed to apply our communicative and collaborative skills to address the outbreak scenario.

The beginning of an outbreak

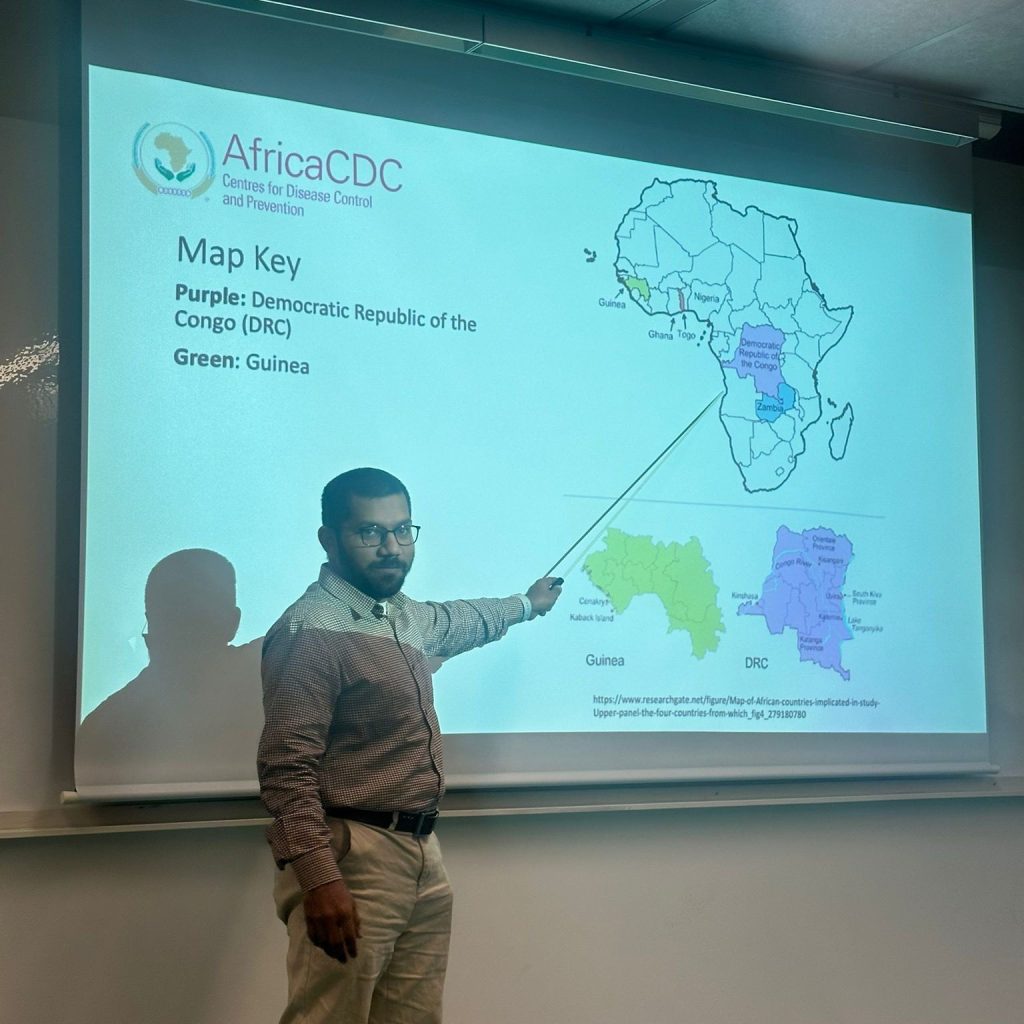

In this workshop, we were assigned to one of four public health agencies to prevent the spread of a fictional Ebola virus outbreak. The four agencies were: ACDC (Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), ECDC (European CDC), the Swedish Public Health Agency (FHM), and the WHO (World Health Organization). I was assigned to the WHO with five other classmates. Before receiving the first set of information regarding the outbreak, we were excited but quite unsure of what to expect.

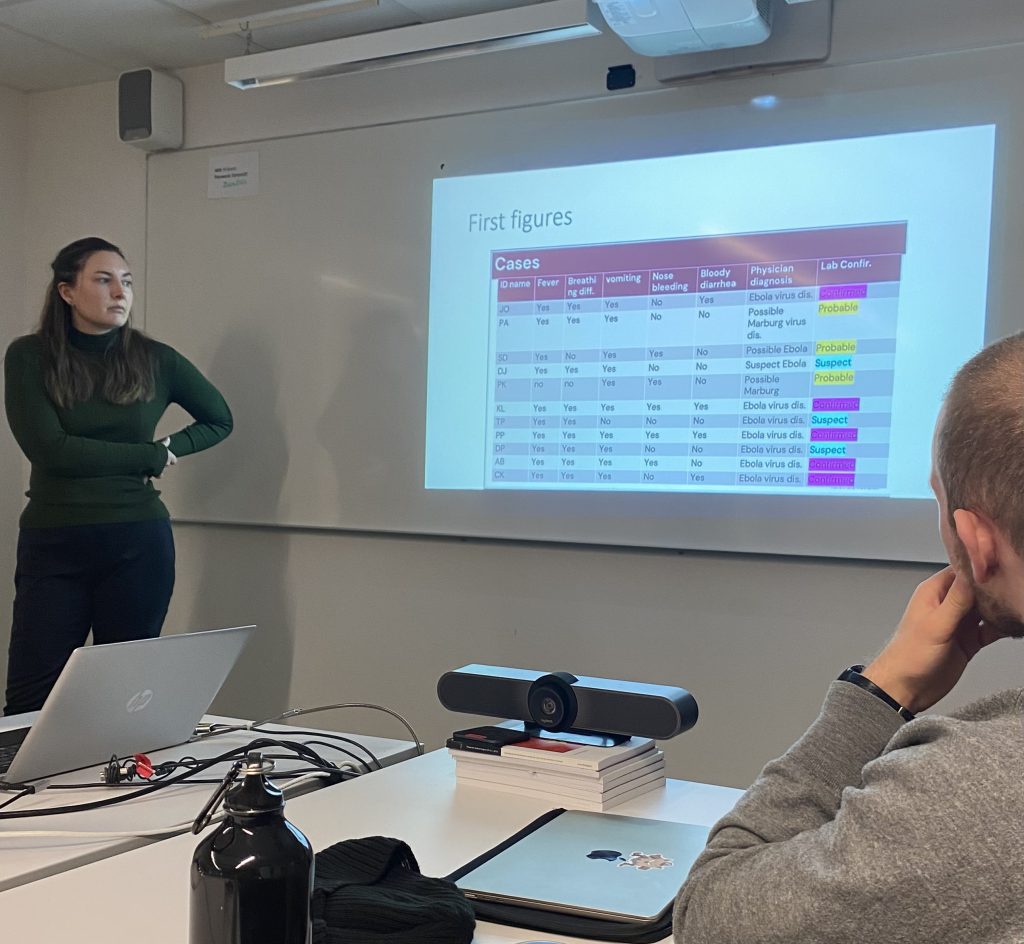

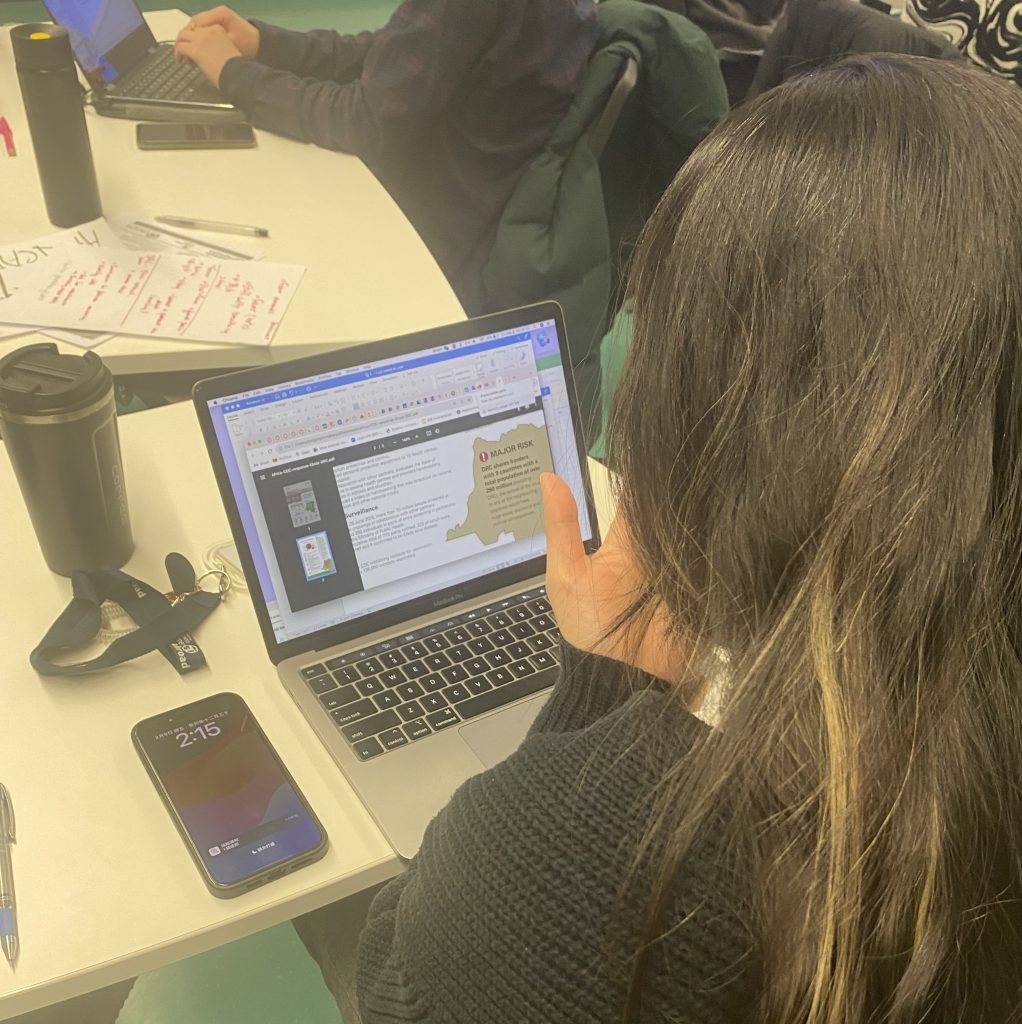

The outbreak scenario was introduced when the FHM group received a call from a “patient”. This patient presented some symptoms of an unknown infectious disease and informed the FHM group that they had visited an animal farm in Malmö a few days prior. Soon, another patient called reporting similar symptoms to the FHM, but this time it was a nurse from Malmö. Within 10 minutes, the FHM had received case counts of the suspected disease. Here, the FHM team made sure to follow a contact investigation script to get information on the patient’s symptoms, travel history, place of residence, and any contact with animals. The ACDC was informed that there were 2 confirmed cases of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). And before we knew it, the outbreak investigation was in full effect.

The scenario

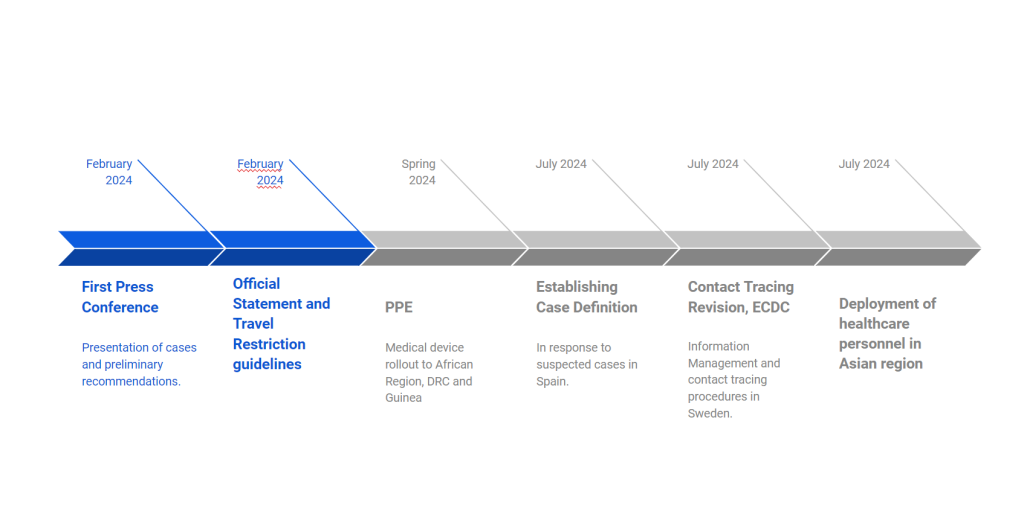

As everything happened so fast and we were all expected to act as public health experts now, the bizarreness of the situation prompted for some collective laughs of disbelief here and there. But to avoid getting overwhelmed, our WHO group decided to sit back and observe the other agencies for a bit. We thought this detached approach was appropriate given that we weren’t responsible for smaller-scaled outbreaks within a country. But within an hour, the case count increased from 2 to 11 in Sweden, and were even higher in Denmark. The DRC and Guinea also saw increases, which prompted the ACDC to request for funding and guidance with PPE (personal protective equipment) from the WHO. At the same time, the ECDC reached out to us for guidance, which finally led to our first press conference.

Press conferences

Throughout the day, each stakeholder held a 3-5 minute long press conference about 2-3 times. The most crucial time points where press conferences were given were at the beginning of the outbreak, when funding/resources were provided, and when more information regarding patient zero was provided.

In our first press conference, we (WHO) reiterated the current case counts in the confirmed global regions and announced that we will be sending necessary medical aid to the DRC and Guinea. This was pretty straightforward information in theory, but it was nerve wrecking to “represent” such a prominent organization talking about a well-known, complex disease.

Each stakeholder answered questions from the press professionally, providing relevant information with correct figures, thereby upholding credibility. Towards the second set of press conferences, we also got to answer questions from the “media”. Our course leader represented well-known news agencies, and posed questions that varied from asking general questions on symptoms and possible restrictions (the “should we be worried” questions), to those that were at times deliberately “unscientific”. I think this was both entertaining and an effective way to train us in our methods of communicating public health issues in plain language.

Post-lunch panic

Before our lunch break, the WHO team decided to provide vaccines and PPE to the ACDC to support the affected areas. After some travel restrictions to and from the DRC into Europe were imposed by support from both the ECDC and FHM, the case counts stabilized somewhat. But we were greeted by a substantial increase in cases within Europe after our break. The ECDC team communicated to our WHO team to request an official case definition of the current disease of interest (Ebola), while we also created air travel restriction protocols together.

As if we couldn’t catch a break, the WHO also received a call from the WHO office in the Asia Region (our course leader called one of our phones and acted as a representative), informing us of outbreaks in Bangkok and Manila. I got a little worried at this point, as this implied a broader transmission route and spread of the disease than I expected!

Despite of the rise in cases in Southeast Asia, we did not formally announce the news during the next press conference until we coordinated some action plans with the Asia office. This was to avoid panicked public responses from the other stakeholders and from lay people, including journalists. While uncertainties ensued for the Southeast Asian region, we also saw positive outcomes reported by the ACDC. Namely, the funding efforts that we initiated before lunch paid off as this allowed for increased vaccine rollouts in DRC and Guinea. This led to a stable decrease in Ebola cases within the African region!

The culprit

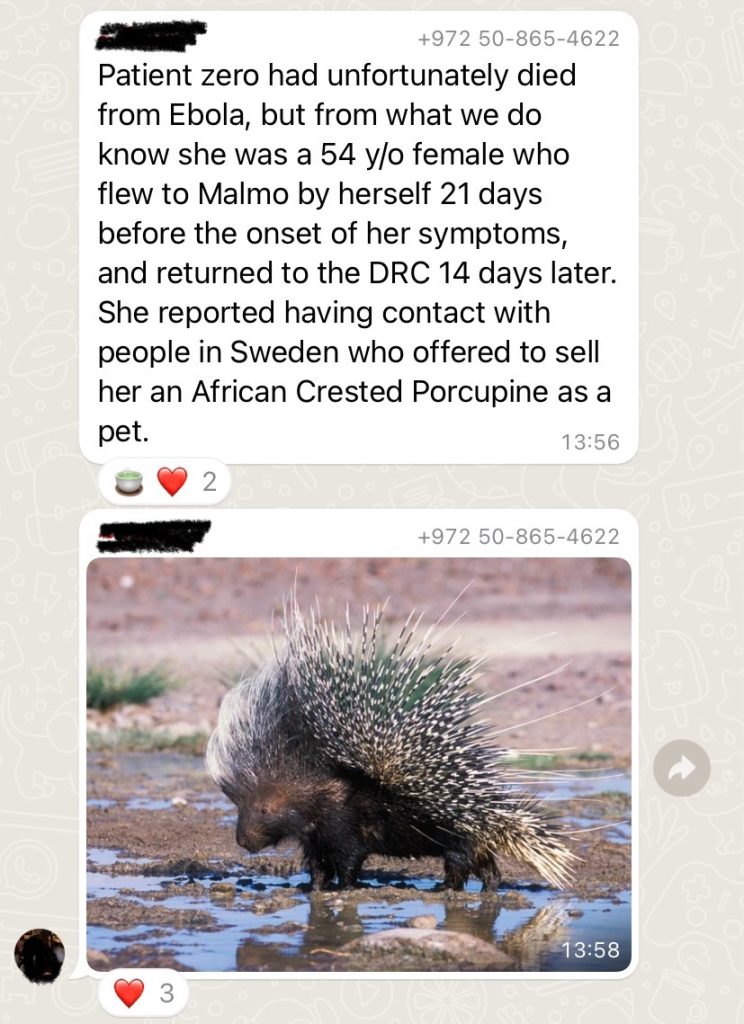

Towards the later portion of the afternoon session, patient zero had been identified by the ACDC. This was announced in our class Whatsapp where patient zero had actually contracted the disease due to interactions with an illegal animal trafficking network (this is fictional!) in Malmö, Sweden. The ACDC group informed us that the patient then flew back to the DRC where her symptoms developed. Hence, the culprit behind our Ebola outbreak was a seemingly harmless (and cute) porcupine.

While this was not part of the information given to us by our course leader, everyone went along with it. Besides, having a wild animal as a reservoir for the disease seemed pretty realistic given our disease, and this plot about an animal trafficking network made the scenario more interesting. For the WHO team, this distracted the other stakeholders from the case counts in the Southeast Asian region, which was a plus!

Future epidemiologists?

Before we knew it, the day was coming to an end. Although it felt a little rushed, we managed to take initial steps in reducing case counts in Bangkok and Manila by deploying 50-100 medical field staff to the cities. After ending the day with a round of summary presentations from every organization, we were finally done for the week. I think we were all very exhausted after challenging our intellectual and communicative limits all day.

But despite all the chaos, panic, and stress, I felt like it was an eye-opening experience. Personally, it was a great way to apply theory into practice, think on our feet, and helped me realize that collaboration and constant communication is an underestimated skill and essence to a successful outbreak response. It made me realize how resilient public health experts were in handling very stressful situations over a prolonged period.

All in all, it was a fun activity that I felt brought the Epidemiology half of the class closer together. Be on the lookout for our classmates as they (hopefully) become successful outbreak-investigating epidemiologists in the near future!

Risa-Public Health Sciences

Hej! I am Risa, a Japanese Master's student in Public Health Sciences starting my studies in 2023 at Karolinska Institutet. Having been interested in the multidisciplinary, globally applicative, and cooperative nature of the public health field, paired with my familiarity with KI’s global reputation, I’ve always had the desire to study at KI. I enjoy curating playlists, petting cats, and going on scenic walks around Stockholm in my free time.

0 comments